'The crisis is already here' – and Congress' inaction is front and center

Data shows workforce shortages are now critical and the harmful impacts to Americans are growing. Industry leaders are begging Capitol Hill to pay attention.

It’s time to talk about workforce shortages again — and no beating around the bush this week. Congress has made no progress and held no hearings this year on any significant proposals to invest in training and hiring more providers, and 83 million Americans already are suffering because of lawmakers’ inaction.

More healthcare organizations, including lobbying groups, and mainstream news outlets are practically begging Congress to act in recent weeks.

‘The crisis is already here’

A report earlier this month by Axios declares “The healthcare workforce crisis is already here,” and they’re correct. If you’ve followed this newsletter for very long, you already know this as well as I do.

But the Axios report notes that complaints about understaffing are growing louder, and more health workers are exiting their jobs. It lists a half-dozen recent surveys of physicians and nurses that all reveal an acceleration of burnout and departures while the number of Americans with no nearby access to primary care is rapidly rising.

"There are 83 million Americans today who don't have access to primary care," Jesse Ehrenfeld, American Medical Association president, told Axios. "The problem is here. It's acute in rural parts of the country, it's acute in underserved communities."

One of the recent surveys cited in the report, by a social networking site for doctors called Doximity, found that 4 in 5 physicians are overworked, and 3 in 5 are considering retiring early, looking for another job or changing careers. Doximity polled more than 2,600 physicians in February and March for its report.

Other key findings:

75% said that reducing administrative burden could meaningfully improve physician overwork and burnout. Research shows that for every hour of direct patient care, physicians spend nearly two additional hours on EHR and desk work during the clinical day, with another one to two hours on clerical work each night.

Nine out of ten physicians said their clinical practice has been impacted by the physician shortage, and 74% described the shortage as “moderate” or “severe.” Only 12% of all physicians surveyed said they have not been impacted by the shortage.

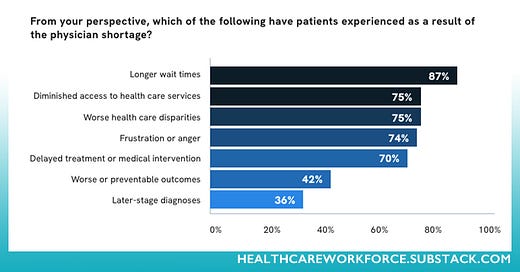

A majority of all physicians surveyed, or 82%, said the shortage has negatively impacted patients:

87% said longer wait times

75% said diminished access to care

75% said worse healthcare disparities

74% said frustration or anger

70% said delayed treatment

42% said worse or preventable outcomes

36% said later-stage diagnosis

Almost all physicians surveyed — 97%! — said they don’t believe that institutional leaders or policymakers are doing anything adequate to address the workforce shortages.

Meanwhile on Capitol Hill: Crickets

Look, I understand that immigration is a touchy topic, but the fact that 83 million Americans can’t see a primary care physician near them in a timely manner demands that our nation’s top lawmakers do something.

It’s not rocket science to understand — or explain to your constituents — that border security and illegal immigration are wholly unrelated to granting visas for credentialed, college-graduate medical professionals from other countries who want to come here and work as doctors, nurses, and nursing home aides.

Yet our current members of Congress — who, statistically speaking, are slacking on the job, passing fewer laws than almost any other Congress in our nation’s history — have accomplished nothing on the dozen or so bills proposing significant solutions for healthcare workforce shortages.

A short list was included in the inaugural edition of this newsletter in July 2023:

Nurse Staffing Standards for Hospital Patient Safety and Quality Care Act of 2023, H.R. 2530 and S. 1113, introduced April 6: Proposes to set limits on the numbers of patients each registered nurse can care for in hospitals.

National Nursing Workforce Center Act of 2023, H.R. 2411 and S. 1150, introduced March 30: Sets out a pilot program to help state agencies, state boards of nursing, and nursing schools establish or expand state-based nursing workforce centers that carry out research, planning, and programs to address nursing shortages, nursing education, and other matters affecting the nursing workforce. Also expands the authority of the Health Resources and Services Administration to establish health workforce research centers and specifically requires that HRSA establish a center focused on nursing.

Strengthening Community Care Act of 2023, H.R. 2559, introduced April 10: Extends funding for the Community Health Center Fund and National Health Service Corps for five years.

More followed in the August 4, 2023 edition, after Senator Bernie Sanders — in a 180-degree change from his “single-payer system” mantra — introduced a massive, bipartisan bill to invest in our healthcare workforce like our lives depend on it (they do):

Sanders’ Primary Care and Health Workforce Expansion Act calls for the U.S. to invest $20 billion a year for five years to “expand community health centers and provide the resources necessary to recruit, train, and retain tens of thousands of primary care doctors, mental health providers, nurses, dentists, and home health workers.”

Spoiler alert: None of those bills have reached the floor of their respective chambers for debate or a vote. Only one proposal, Sanders’, has been discussed at a committee hearing and made it back to the chamber. To be clear: it was “placed on the Senate legislative calendar” back in November. No action reported since. The other significant bills proposing to address healthcare labor gaps were introduced and sent to committee — and no further hearings or actions have been recorded on them either.

It’s not just health workers who are fed up; provider groups are demanding solutions now too

And now the healthcare organizations with the loudest voices and the most influence are publicly pleading for action, too.

Last week, the State Department announced that no more EB-3 category visas would be granted to healthcare workers seeking to emigrate from key countries such as the Philippines for the rest of the fiscal year; the annual limit has been reached, apparently.

This is horrible news for healthcare employers, especially nursing homes; our health system relies heavily on nurses who come to the United States to fill healthcare staffing shortages.

“Restricting EB-3 visas for immigrant healthcare workers will create significant backlogs and hamper the development of worker pipelines into healthcare,” according to a coalition of lobbying groups and provider associations formed late last year by the American Association of International Healthcare, the American Hospital Association, and others.

"We're reaching a dangerous inflection point where acute nurse staffing shortages feed burnout in a force-multiplying cycle that grows worse every day," AAIHR President Patty Jeffrey said in a statement. "Until we can correct capacity issues that force nursing schools to reject thousands of qualified applicants annually, international nurses will remain essential to safe nurse staffing. This latest visa freeze halts the flow of qualified international nurses when American hospitals need them most, and the only way to correct it is through congressional action."

AAIHR noted that the State Department’s announcement landed shortly after HHS’ new nursing home staffing rule was finalized; its requirements for nursing homes to have sufficient nurses on duty mean that over 20,000 new RNs will need to be hired in the next several years.

Immigrant nurses can help alleviate our workforce shortages a lot — in fact, they already have helped a lot, and the need is nowhere near met.

Advocates for nursing homes have consistently pushed for more immigrant nurses to be granted the right to work in the US. About 25% of all U.S. nursing home care workers are immigrants, and they have been a vital foundation for the workforce. They are far more likely to be retained by employers than their co-workers who are American citizens, according to McKnight’s.

Begging for action on a bill that all parties seem to agree on

Those challenges could be partially addressed by the proposed Healthcare Workforce Resilience Act — bipartisan legislation introduced and sponsored by members of both political parties in both houses of Congress.

The coalition wants Congress to pass the Healthcare Workforce Resilience Act, which would authorize an additional 40,000 visas for nurses and physicians while protecting American workers in similar jobs. “Given long-term care’s widespread shortages of workers, there is little chance that bringing in more immigrant long-term care nurses would displace U.S. workers,” McKnight’s noted.

And there are still more bills introduced since winter with bipartisan support yet zero legislation action:

Welcome Back to the Health Care Workforce Act: Introduced April 9 in House and Senate sent to committee, no action recorded since. This bill authorizes the Secretary of Health and Human Services to award grants for career support for a skilled, internationally educated healthcare workforce.

Health Care Workforce Innovation Act: Introduced February 9, it authorizes the HHS Secretary to establish a grant program for “eligible entities to support and develop new innovative, community-driven approaches for the education and training of allied health professionals, with an emphasis on expanding the supply of allied health professionals located in, and meeting the needs of, underserved communities and rural areas.” Sent to committee, no legislative action recorded since.

Anybody else wondering how bad our healthcare system’s workforce shortages must get for Congress to take meaningful action?

I’m just gonna leave this right here: How to contact your representatives in Congress.

Shout-out to HWR sponsors

The Healthcare Workforce Report newsletter is generously supported by MedCerts.

For information on supporting HWR, email HealthcareWorkforce@substack.com.